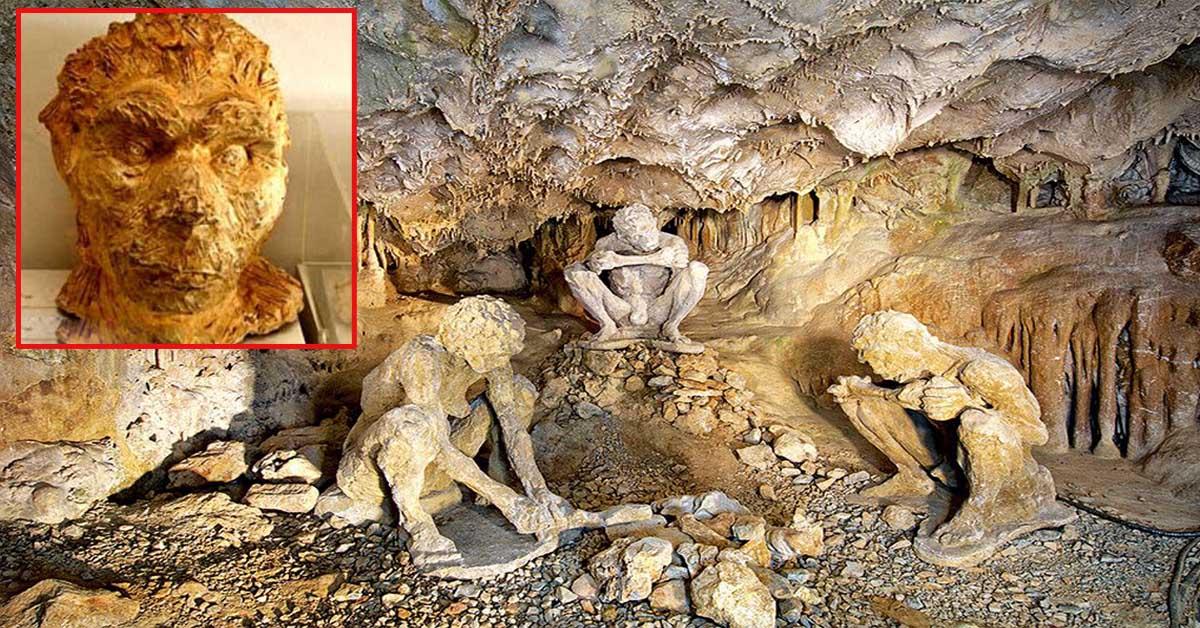

Nature, a capricious architect, reveals its randomness upon entering Petralona Cave, formed in the limestone of Katsika Hill a million years ago. Dubbed “the red-rock cave” for its bauxite-tinted stones, this cavern spans 10,400 m², adorned with stalactites, stalagmites, and various formations. Discovered in 1959, it has become Greece’s most significant cave, boasting Europe’s richest fossil collection and housing the oldest human remains found in the country some 50 years ago.

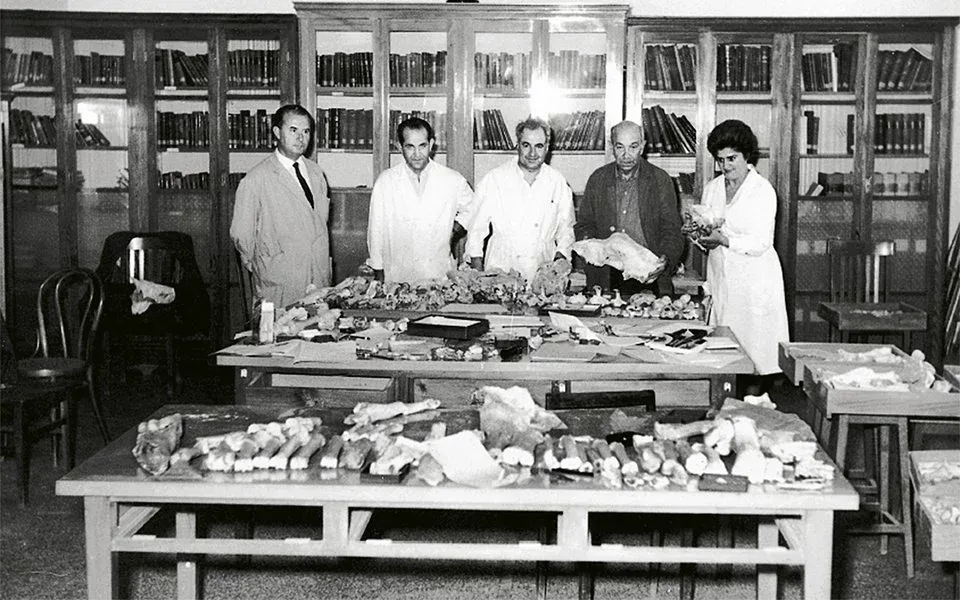

Initially unearthed by Petralona residents, the cave drew attention when they presented petrified animal remains to Professor Petros Kokkoros. Excavations ensued, uncovering passages and artifacts, turning the cave into a geological and anthropological treasure trove. In 1960, a fossilized human skull, believed to be 200,000 years old, was found among diverse animal fossils, marking a pivotal discovery in human evolution.

Known as the “Parthenon of paleontology,” the cave continues to be researched by top paleoanthropologists globally. While a man-made tunnel facilitates tourist access to its intricate formations and cave art, the question of human habitation remains unanswered. The cave’s proximity to an Anthropological Museum and its role as a repository for diverse fossils contribute to ongoing scientific exploration, promising revelations through international collaboration and advanced techniques.

Dr. Evangelia Tsoukala, a paleontologist from Aristotle University, anticipates further discoveries in Halkidiki, highlighting findings such as a well-preserved Mesopithecus pentelicus skull and Deinotherium teeth. The Anthropological Museum showcases artifacts from various northern Greek sites, complementing the Geology-Paleontology Museum’s display of the famous human skull and global discoveries.

Petralona Cave stands as a testament to the mysteries of human evolution and the continuous unveiling of Halkidiki’s fossil-rich history, inviting exploration and collaboration for a deeper understanding of the past.