The intriguing possibility of resurrecting an extinct horse highlights difficult questions and contradictions of modern wildlife thinking.

Would a horse cloned from a species extinct for more than 10,000 years, be a “native” if returned to its original home? If the ancient horse species were “native”, would that mean that later-arriving species were “invasive”?

On the other hand, if the horse ceased to be native to those places from which it disappeared, and is now “exotic” or “invasive” in those locations, why isn’t that also true of deer, sheep, bison, elk, moose, and other species we are restoring to places from which they also disappeared? There are a lot of opinions, but no science-based answers to those questions.

For millions of years, animals have come, gone, and returned to the Earth’s wild places. Because change was constant, animal and plant communities varied greatly over time.

The horse shown below might have been found in America, where all horses evolved. Horses and their ancestors were American natives for 50-million years, long before any of the other animals mentioned above crossed over the Bering land bridge from Asia.

Horses—and many other species—disappeared from America when early human hunters arrived around 12,000 years ago. They have been back in America for 500 years, where many say they are “invasive exotics” that have no place among American wildlife.

After climate change, the most discussed environmental issue is the so-called invasive species crisis. Invasive species biology rests on the mistaken belief that the animals and plants found on our planet about 500 years ago represented a stable, ideal balance of nature. In fact, this condition never existed.

Because of this widely held misconception, the fake science of invasive species biology dominates discussion and dictates public policy and land management strategies. Invasive species biology has prompted a raging war on weeds and wildlife which attempts to reshape and confine ever-changing Mother Nature according to the collective misperceptions and preferences of wildlife “managers”.

Scientists in the Yakutsk region of Siberia have managed to extract samples of liquid blood from a 42,000-year-old foal that was found embedded in permafrost back in 2018. The scientists are hoping to collect viable cells for the purpose of cloning the extinct species of horse.

The male foal was discovered in the Batagaika depression on August 11, 2018. Permafrost left the remains in remarkably good shape, raising hopes that its cells could be extracted. The specimen is thought to belong to an extinct species of horse known as Lenskaya breed (also known as the Lena horse), as the Siberian Times reported last year.

A collaboration between North-Eastern Federal University in Yakutsk and the South Korean Sooam Biotech Research Foundation is currently analyzing the remains with the explicit intent of cloning the prehistoric horse. To do so, however, the researchers would have to extract and grow viable somatic cells—something they haven’t been able to do just yet. More than 20 attempts to grow cells from the animal’s tissue have all failed. A detailed analysis of the horse began last month, with work expected to last until the end of April.

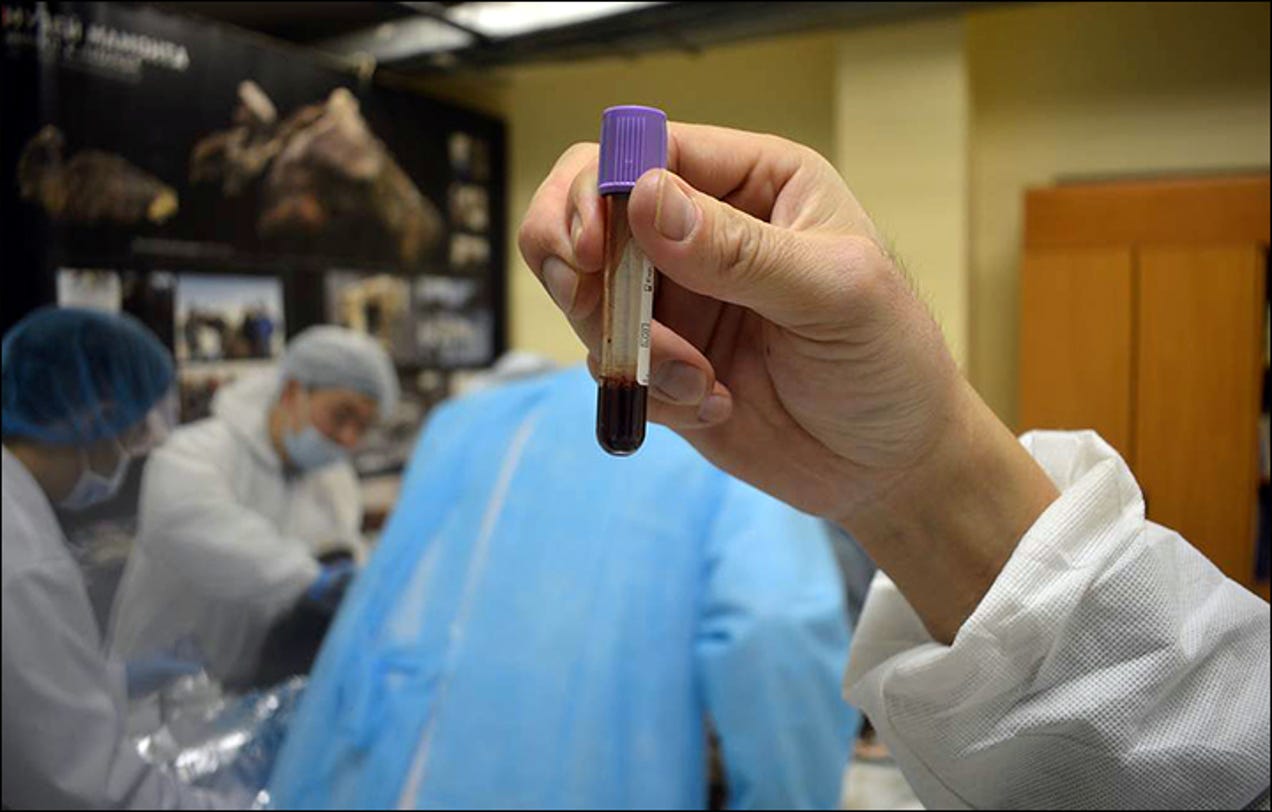

As the Siberian Times reported earlier today, the researchers have now managed to extract samples of liquid blood from the specimen’s heart vessels, which were well-preserved owing to favorable burial conditions and the permafrost, according to Semyon Grigoryev, head of the Mammoth Museum in Yakutsk. It’s not clear if viable cells can be grown from the blood sample.

In an interview with the Russian news agency TASS, and as relayed by the Siberian Times, Grigoryev said the autopsy has shown “beautifully preserved organs” and muscle tissues preserved with their “natural reddish color.” In addition, the foal still exhibits hair on its head, legs, and parts of its body. Having “preserved hair is another scientific sensation as all previous ancient horses were found without hair,” said Grigoryev. When alive, the animal featured a bay color, with a black tail and mane.

“Our studies showed that at the moment of death the foal was from one to two weeks old, so he was just recently born,” said Grigoryev. “As in previous cases of really well-preserved remains of prehistoric animals, the cause of death was drowning in mud which froze and turned into permafrost. A lot of mud and silt which the foal gulped during the last seconds of its life were found inside its gastrointestinal tract.”

The conserved nature of the horse, plus the blood sample, signifies it as “the best preserved Ice Age animal ever found in the world,” declared Grigoryev. Well, “best preserved” is in the eye of the beholder, but Grigoryev has a strong case. Back in 2013, Russian scientists found liquid blood in the remains of a 15,000-year-old wooly mammoth. The blood pulled from the foal is 27,000 years older.

As noted, a major goal of this collaboration between NEFU and Sooam Biotech is to revive this animal through the processes of cloning (as an important aside, Sooam Biotech is in the business of cloning pet dogs in South Korea, and its lead researcher is Hwang Woo Suk, the controversial geneticist accused of several egregious ethics violations during the 2000s). Apparently, the work “is so advanced” that the team is looking for a surrogate mare “for the historic role of giving birth to the comeback species,” the Siberian Times reports with its typical unbridled enthusiasm.

Clearly, there are some serious ethical and technological issues that need to be addressed. Reviving species is controversial for a number of reasons, including the diminished quality of life for the clone (which will be subject to experiments during its entire life), the problem of genetic diversity and inbreeding, and the absence of an Ice Age habitat to host the revived species, among other limitations.

The Russian-Korean collaboration is also trying to clone a woolly mammoth, and the research gleaned from the foal research could be used as groundwork for that pending experiment. The resurrection of an extinct species, whether we like it or not, may happen sooner than we think.