Researchers have described a Japanese mosasaur the size of a great white shark that terrorized Pacific seas 72 million years ago. Credit: TAKUMI

In a significant paleontological discovery, the Wakayama Soryu, a mosasaur the size of a great white shark, has been identified from fossil remains found in the Blue Mountains of Mexico. This fearsome predator lived 72 million years ago, showcasing unique adaptations that set it apart from other mosasaurs.

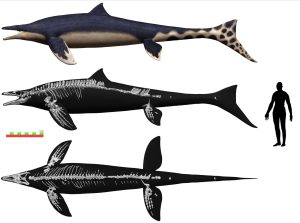

The specimen, discovered along the Aridagawa River in Wakayama by co-author Akihiro Misaki in 2006, includes extra-long rear flippers that might have aided propulsion alongside its long-finned tail. Unlike other mosasaurs, it had a dorsal fin similar to a shark’s, aiding in quick and precise turns in the water.

University of Cincinnati Associate Professor Takuya Konishi and his international co-authors placed the mosasaur in a taxonomic context in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. Named for its discovery location, Wakayama Prefecture, the Wakayama Soryu, or “blue dragon,” is rooted in Japanese folklore, where dragons are legendary creatures that became aquatic in mythology.

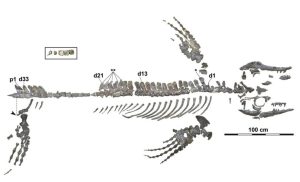

Misaki was initially searching for invertebrate fossils called ammonites when he found an intriguing dark fossil in the sandstone. Upon closer examination, it revealed a vertebra, part of a nearly complete mosasaur skeleton, the most complete ever found in Japan or the northwestern Pacific.

Konishi, who has dedicated his career to studying ancient marine reptiles, noted that the Japanese specimen’s unique features defy simple classification. Its rear flippers are longer than its front ones, a trait unseen in other mosasaurs, and its crocodile-like head adds to its distinctiveness.

Mosasaurs were apex predators in prehistoric oceans, contemporaries of Tyrannosaurus rex, and victims of the mass extinction event that eradicated most dinosaurs. The Wakayama Soryu, with nearly binocular vision, was a lethal hunter.

Researchers placed the specimen in the subfamily Mosasaurinae and named it Megapterygius wakayamaensis, meaning “large winged” to reflect its enormous flippers. These paddle-shaped flippers might have been used for extraordinary locomotion, unlike any other animal, challenging our understanding of mosasaur swimming mechanics.

Konishi speculated that the large front fins helped with rapid maneuvering, while the large rear fins provided pitch for diving or surfacing. The tail likely generated powerful acceleration while hunting fish. Unique to mosasaurs, the Wakayama Soryu had a dorsal fin, suggested by the orientation of the neural spines along its vertebrae, resembling the structure in harbor porpoises.

A team of researchers spent five years meticulously removing the surrounding sandstone matrix from the fossils. They also created a cast of the mosasaur in place to document the skeletal orientation before excavation.

In conclusion, the Wakayama Soryu represents a profound breakthrough in our understanding of prehistoric marine reptiles, promising to reshape our knowledge of mosasaur adaptations and ancient ocean ecosystems.